2.2 The Cauld lad of hylton

Brownie, Poltergeist or murder most horrid, who is the Cauld Lad of Hylton and why is he so cold?

In this episode, we’re debating an incredible case of the Cauld Lad. Well known to our northern listeners, this story comes from Hylton Castle in Sunderland with two very different retellings.

In the first, Robert Hylton, 13th Baron Hylton, either accidentally or purposefully murdered his stable boy - Roger Skelton. In a panic, Hylton concealed the boy’s body by dropping it down a well where the skeleton was discovered some years later. Reports indicate that court records from 1609 show Hylton was tried and acquitted of murder when a servant corroborated the story that the Baron had been scything grass and accidentally struck Skelton in the leg.

But despite the acquittal, rumours persisted that Hylton had murdered Skelton either by cutting the boy down in a rage over his laziness (although one rumour had it that Skelton was caught with the Baron’s daughter) or by skewering him with a pitchfork.

Accident or murder, upon the discovery of Skelton’s bones residents of the castle began to report hearing the cries of a boy at night:

“Aa’m cauld! Aa’m cauld”

And would hear terrible crashes and smashes, waking to find rooms left tidy the previous evening in a mess and places already a mess, cleaned and tidied as if a servant had done their duty. Items would vanish and even fire embers were discovered scrapped from the hearth and shaped as if a child had laid upon them.

Soon, suspicions grew that either Skelton’s restless spirit haunted the castle or that a Brownie had taken up residence.

Brownie or Spirit?

In British and Scottish folklore, a Brownie is a type of house fairy or fae. They could either prove helpful, often tidying and cleaning, or unhelpful if annoyed with the human occupants in the home. An angry Brownie would make a terrible mess, while one kept happy with saucers of milk and bread would be a great boon to a household.

In the fairytale version of the Cauld Lad, where the nuisance is a Brownie, a much beleaguered cook and his wife stay up all night to discover who is destroying the kitchen. To their surprise they see a small, hairy boy-like creature that complains he’s cold and sings:

Wae’s me, wae’s me,

The acorn’s not yet fallen from the tree,

That’s to grow the wood,

That’s to make the cradle,

That’s to rock the bairn

That’s to grow to the man

That’s to lay me!

Taking pity on the creature, the cook’s wife makes a cloak for the Cauld Lad and leaves it for him to discover. Upon putting on the cloak the Lad - as Brownies are known to do when gifted with clothes - becomes so thrilled that he abandons Hylton Castle with the declaration:

“Here's a cloak and here's a hood, the Cauld Lad of Hylton will do no more good."

And vanishes.

Or does he?

Stories of the Cauld Lad still persist to this day, with visitors to the gatehouse, which is all that now remains of the castle, still reporting items moved or vanishing and the ghostly cries of a boy in the night.

2.1- Sabrina of the Severn

A princess, a nymph, the goddess of the Severn. Just who is Sabrina? And where did she come from?

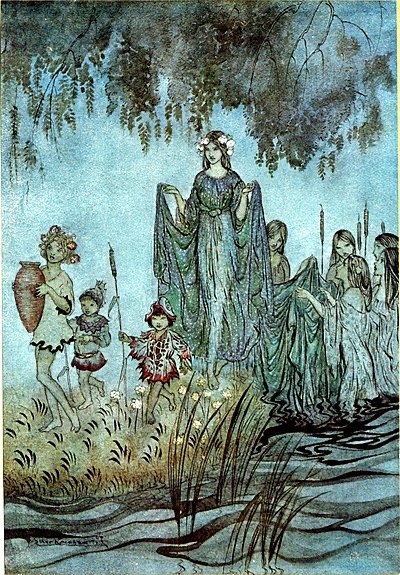

For the start of season two, we’re looking at the tragic, haunting tale of the princess-turned-water sprite Sabrina. This story comes to us via our old friend Geoffrey of Monmouth as part of the long cycle that tells of the founding of Britain. Sabrina’s death and reawakening have served as inspiration for artists throughout the centuries. Let have a look at some of the sources, inspiration and transformations the story has undergone since it was first published in around 1136.

Brutus, Cornieus and Gwendoline

Sabrina’s story starts at the end of the reign of the famous Brutus, who we have seen before in the tale of Cormoran the Giant. Like many British medieval writers, Geoffrey of Monmouth seems to be trying to give Britain the legitimacy of a connection to the ancient worlds of Greek and Roman Literature. In Historia Regum Britanniae, he tells of the Trojan Brutus’s conquest of Britain, the setting up of the kingdoms of Britain under Brutus’s lieutenant, Cornieus, and his sons Locrinus, Camber and Albanactus.

The only one of these men we’re interested in is Locrinus, who apparently becomes king of Loegria (England) after his father’s death. Betrothed to Cornieus’s daughter Gwendoline, he falls in love with a captured German princess and proceeds to have a daughter with her, Hafren.

When Cornieus dies, Locrinus sets aside Gwendoline in favour of the German princess and her daughter. In the inevitable war that follows, Hafren and her mother are captured by Gwendoline and thrown into the river to drown. Thus a legend is born.

Hafren or Sabrina?

In Geoffrey’s telling the unfortunate daughter of Locrinus is named Hafren, which is one of the Welsh versions of the name of the River Severn. In fact, the Romanised name Sabrina had been used for both the river and the girl as early as the 2nd century AD. As with almost everything else in the Historia Regum Britanniae, the quasi-historical tales of Hafren is Geoffrey’s own re-telling of a much older legend which appears to have predated the Roman occupation of Britain. And as with the story of Vortigern and Ambrosius, Geoffrey seems to have opted for Welsh names over the Latin or Celtic.

But it is impossible to tell whether the girl or the name of the river came first. Is the story of Sabrina just a way to explain how the river got its name? Or is this the personification of the waters by a people who believed that rivers and lakes were the entrance to another world?

The British Celts used waterways as sites of worship, as evidenced by the huge number of votive offerings found in rivers all over England. But the Severn seems to be almost unique in being named after its protecting goddess. Most other river names, such as the Avon, Wye, Wyre and Don, are derived from Celtic words for water. And others, such as the Thames, Teme and Tamar, seem to be dervided from Celtic words for ‘dark’, which is perhaps a description of their waters.

Sabrina Fair

The story of Sabrina is so irresistibly tragic that it comes as no surprise that it has inspired writers and artists throughout the centuries. Edmund Spencer includes as passage about the sprite Sabrina in ‘The Faerie Queen’ and John Milton used the goddess in his masque ‘Comus’, which is about chastity. In the story, he presents the transformed princess as a divine nymph who saves a virgin from being seduced by a villain. If you haven’t read it then there is a full copy available here. The imagery paints a wonderful illusion of divine beauty:

In twisted braids of lilies knitting

The loose train of thy amber-dropping hair;

——Listen for dear honour's sake,

——Goddess of the silver lake,

Listen and save!

In the twentieth century, Milton’s words would lend themselves to the play Sabrina Fair which then became the icon film starring Audrey Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart.

1.8- A Carol for Christmas

Wassail, wassail! It’s time for some festive cheer and two stories inspired by our favourite Christmas carols.

For the final episode of our first season, we took inspiration from the stories behind some of our favourite Christmas Carols. Read on to discover what we found when we went digging into the famous Roud Index.

In the Roud

This week’s episode was supposed to focus on the story of the water nymph Sabrina. But the closer we got to recording, the more I felt that we needed something a bit more Christmassy to finish off the first series of the podcast. Enter inspiration in the form of the folk music podcast In the Roud. This fascinating pod, presented by folk singer Matt Quinn, explores the folk songs collated by Steve Roud. It is well worth a listen to hear the sheer breadth of knowledge about British folk music and to hear some of the icons of the folk scene perform. I would highly recommend starting with episode 0, where Steve Roud discusses the purpose of the index and how it works.

We’ve been obsessed with this podcast for a while and so we decided to take a look at some traditional English Christmas Carols from the Roud Index and see if we could find some festive tales to tell.

The Gloucestershire Wassail (Roud 209)

For me, there could only be one choice for the ultimate Christmas Carol. The Gloucestershire Wassail has it all: camaraderie, drinking, collective revelry and funny local folk customs. As Wyrd Folk is based in Gloucestershire it seemed rude not to include the carol in our first annual celebration of English Christmas carols.

Wassail is having something of a revival of late, thanks to the many burgeoning folk societies and new morris sides. Wherever there are apple orchards in abundance, there’s wassail. But did you know that there are two types of wassail? Most people are aware of the wassail that takes place in January to help bless and protect the apple harvest for the coming year. But fewer people are aware of the Christmas Eve tradition of the house-to-house wassail.

If you look at the lyrics to the Gloucestershire Wassail, it is all set out for you. ‘Wassail, wassail all over the town.’ When this song was collected from little villages and towns all over Gloucestershire in the early twentieth century, it was still the practice for revellers to go from house to house on Christmas Eve with their wooden wassail bowl to bring cheers and dance (and take away any food and booze people could give) to begin the Christmas celebrations.

Roud 209 is one of the songs in the Roud Index which has a seemingly infinite number of versions. While the tune remains almost the same, the lyrics seem to have been adapted to whoever the singer was addressing. And so we have the story of many a Gloucestershire village. Have a look for yourself on the Roud Index pages of the Vaughn Williams Memorial Library website.

There’s also an episode about Roud 209 coming soon on the In the Roud Patreon page.

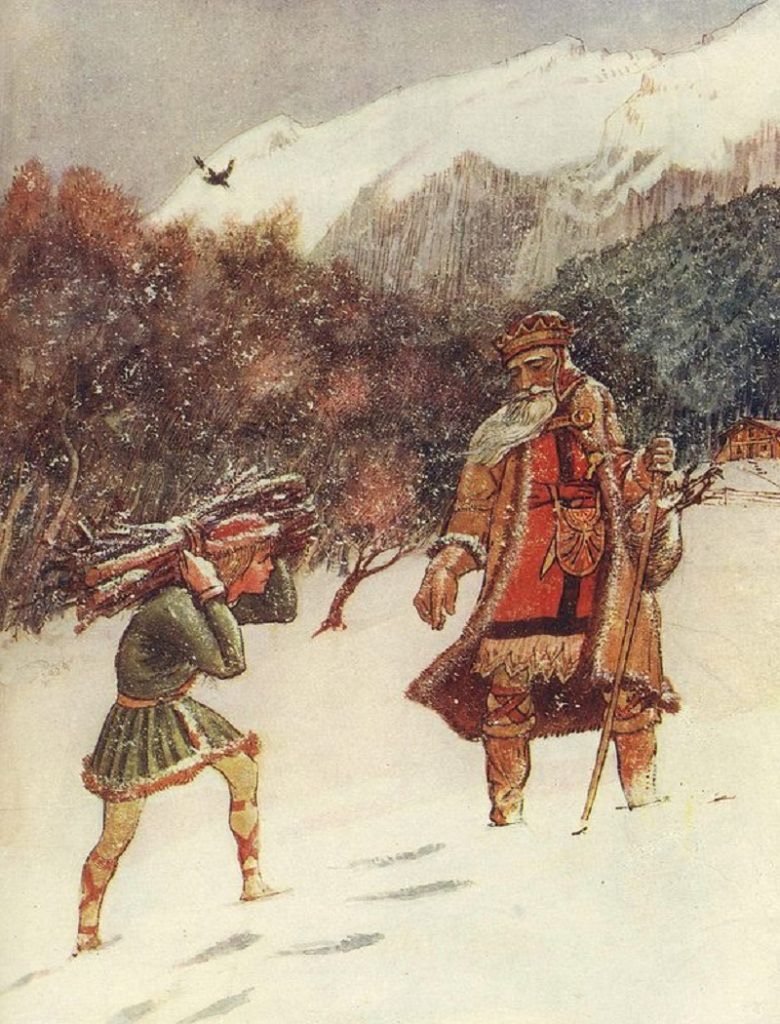

Good King Wenceslas (Roud 24754)

Sam’s choice is a much more recognisable song but with a much stranger history. Virtually anyone in England can sing snatches of the story of Good King Wenceslas’s tale of Christian generosity. But very few people know the dark and ancient origins of the song.

Firstly, Wenceslas is a duke, not a king. In fact, he was the duke of Bohemia (now part of the modern Czech Republic).

And secondly, he was a popular folk hero whose memory was preserved after his untimely murder. Slain by his own brother, Wenscelas had such a reputation for generosity, especially with the poor and the hungry, that a cult very quickly grew around his memory.

But it wasn’t until 1853 that an English Catholic hymn writer took the legends around Wenscelas, turned them into the lyrics we know today and married them to a 13th-century spring carol called ‘tempus adest floridum’. An instant classic was born, bringing word of the Christian spirit of Duke Wenscelas to a new modern audience. Have a look for yourself by taking a scroll through the Roud Index.

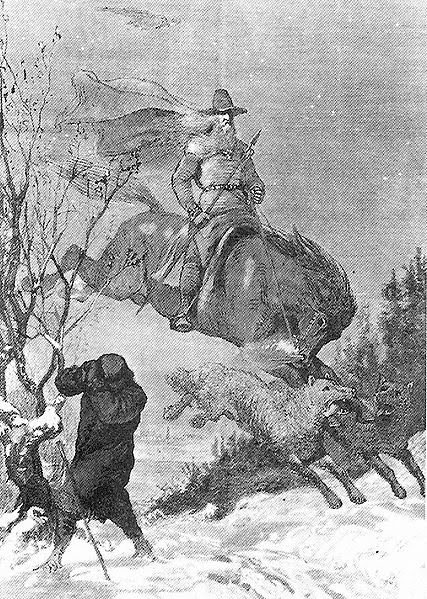

1.7- Harry ca Nab and the halesowen wild hunt

Do you dare walk the Winter woods when Harry is on the hunt?

In this week’s episode, we explored the tale of the cursed Halesowen huntsman, Harry ca Nab. Just like young Lambton in the tale of the Lambton Worm, our hero is roundly punished for breaking the sabbath to indulge in his favourite pastime. But unlike Lambton, he has no chance to redeem himself. Come with us this week to meet the Devil’s own huntsman.

Hell’s Own

Many places across the UK have wild hunt legends attached to them, each with its version of who leads the hunt and when they ride. What attracted us to the Harry ca Nab story was that it is very much a Winter’s tale.

Some say that Harry and his Gabriel Hounds ride out from the local town of Halesowen- sometimes taken to mean Hell’s Own- to hunt boar over the Clent and Lickey hills. It is more likely that the town’s name is a combination of the Anglo-Saxon word for valley ‘halh’ and a Welsh prince called David Owen, who was gifted the area.

Other parts of the legend suggest that Harry was once a local landowner who chose not to respect the peace of Sunday because his lust for the hunt was more important than religious observance. But is it really a punishment to curse someone who loves hunting to become an immortal huntsman for the rest of eternity?

Devil or Saviour?

One of the classic conflicts in Wild Hunt legends is whether the hunt rides for good or for evil. Some huntsmen, like Harry ca Nab, are said to work for the devil. Some hunts are supposedly led by Old Nick himself. These hunts often ride out in the winter and at night. A meeting with them is usually certain doom for the poor soul who strays into their path.

But these are Christian traditions, so of course the hunt is associated with evil. In older Celtic traditions the wild hunt is often led by the gods. The Anglo-Saxons believed that the hunt was led by Woden, father of the gods. And in Welsh mythology, the hunt is led by the lord of the dead, Gwyn Ap Nudd. While neither of these figures is entirely benign, you are a lot more likely to get away with your life if you meet them than if you come face to face with Old Scratch.

Song of the Huntress

Another inspiration for the episode was Lucy Holland’s brilliant novel ‘Song of the Huntress’. We met Lucy briefly at the Butser Ancient Farm Book Festival, where we spoke about her inspiration for writing the novel. Wild hunt legends are often solely focused on men, but Lucy has pulled the women of the Anglo-Saxon period into sharp focus, giving them the opportunity to demonstrate to the reader that women had a role in the cut and thrust of Britain’s past too. We can really recommend it for anyone who loves a good wild hunt tale and a bit of British history.

1.6- The Dragons of Dinas Emrys

The timeless Welsh tale of magic, Merlin and dragons.

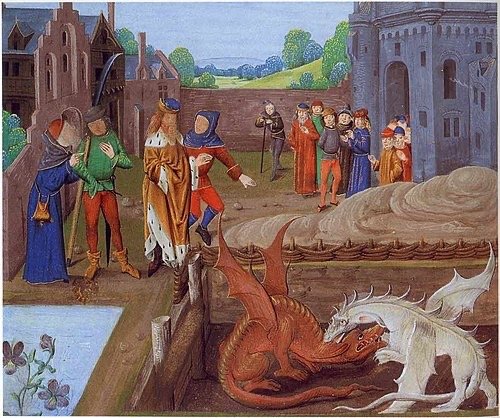

This week, we delve into the magical world of dragons, druids and destiny as we look at two versions of the classic Welsh legend of the Dragons of Dinas Emrys. This tale is a must for anyone who loves a good Arthurian legend.

Emrys, Ambrosius or Merlin?

One of the things that inspired us to write about the Dinas Emrys is the vital role it plays in the origins story of one of the nation’s most beloved legendary figures, Merlin. The tale of the boy who solves the riddle of Vortigerns collapsing fortress and frees the dragons comes to us from two historical sources. The first of these is the Historia Brittonium of Nennius in around 828 AD(which you can read in full here) and the second is the medieval The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, who essentially invented the genre of Arthurian legend.

Both texts tell a similar story, both of them focus on Vortigern as either bad or foolish and both texts agree that it is a special boy who tells the king about the dragons fighting underneath the hill. But each author has chosen a different name for the boy. Nennius calls him Ambrosius (or Ambrose) and explains that his father was a Roman consul- giving him a lovely Roman sense of authority in the eyes of that author.

And Geoffrey, who is apparently working off an ancient British text that he refuses to show anyone else and of which he possesses the only copy, refers to the boy by the name Emrys, which is then transposed into the name Merlin.

Both names mean ‘immortal’ but what is interesting is that Nennius chooses the Greek word ‘Ambrose’, whereas Geoffrey, for all his other faults, chooses the Welsh ‘Emrys’.

Mountains and Waterfalls

A few years ago we took a trip to Gwynedd in the early spring with the specific goal of climbing Dinas Emrys and inspecting what was left of the fortifications. The day was raw but sunny, and the streams and waterfalls were full to bursting with winter rain.

It remains one of the most magical experiences of my life. Not only because of the beauty of Eyri or the wonder of the seemingly endless waterfalls and spring but because the landscape is so breathtaking, so steeped in magic that it just carries you away. It was all to easy to look at the craggy remnants of the little fortress on the hill and the giant portal stone by the pool below the summit and imagine dragons.

If you are ever in North Wales, follow in our footsteps and find Dinas Emrys. You won’t regret it.

Diana Wynne Jones

The third and final inspiration for the episode somes from one of my favourite authors. No one writes magic for children as well as Diana Wyne Jones. For both Sam and I, she was the writer who first inducted us into the mysteries of Welsh mythology. In fact, I still regularly re-read her books. Many people will be familiar with her novel ‘Howl’s Moving Castle’ because of the Studio Ghibli film (which is great but nowhere near as good as the book).

However, not many modern readers will be as familiar with one of her best novels, ‘The Merlin Conspiracy’ which weaves the legend of the white and red dragons into a pacy duel narrative that crosses worlds and timelines. From Gwyn Ap Nudd to the magic of flowers, Jones manages to squeeze into one tight narrative hundreds of tiny details from British and Welsh folklore. It is classic fantasy fiction at its best. We cannot recommend it enough.

1.5- The Vampire of Croglin Grange (Short)

Fake or folktale? The Vampire of Croglin Grange is a rip-roaring horror story, but is it a traditional folktale or just the fevered imaginings of a vampire-obsessed writer looking to spice up his autobiography?

Is it a zombie? Is it a lunatic? No, it’s the infamous vampire of Croglin Grange. In this week’s short Nikki explored the origins of this popular Cumbrian vampire tale and asks ‘is this folklore'?

Augustus Hare- The Last Victorian

Everything starts with Augustus Hare because we wouldn’t have the story of the vampire without him. Born in Rome in 1834, Hare was adopted by his maternal aunt and brought up in relative seclusion. He seemed to have had an extremely close bond with his adoptive mother and after she died, he was responsible for arranging her memoirs for publication. We won’t tell you the whole story here because Hare does it (at great length) in his autobiography ‘Story of My Life’, which runs to two books of three volumes each.

If you’re looking for the story of The Vampire of Croglin Grange then you’ll need to skip straight to the second book of his musings, which was published in 1901. Both volumes are available here at Project Gutenberg. The entry you’re looking for is dated ‘‘June 24 (or 24th June) in the At Home and Abroad volume.

This entry is the first recorded telling of the now infamous story of The Vampire of Croglin Grange. It is well worth reading in its entirety, especially in the context of the rest of Hare’s writings.

In this entry, Hare recounts with his usual bonhomie and defference to anyone with a title, a dinner given by Lord Ravenswood in Lodndon. At the dinner, the guests enter into a bit of a storytelling competition, with various members of the party telling chilling tales of death omens and hauntings to liven up what I imagine to be quite a dull evening.

Step forward one Captain Fisher, the fiance of Lord Ravenswood’s Daughter Victoria, who supposedly tells Hare the tale of The Vampire of Croglin Grange. It is a ripping yarn and extremely well remembered by Hare, especially if you considered that he was told this tale in 1874 and doesn’t write it down for his autobiography until 1900! I don’t know about you but I struggle to remember what happened last week, never mind the intricate details of a story I was told at a dinner party twenty-five years ago.

Any half-reasonable person would look at just this fact and begin to question how much of Hare’s tale is really the same as that told to him by Captain Fisher and how much is Hare simply inserting quite a good horror story into his amazingly dull autobiography to add some late Victorian gothic thrills. Since no one bothered to track down or ask Fisher about this during his lifetime, we may never know if this is the story as he told it. So instead we (like every other folk researcher for the last 120 years) will just have to look at the readily available evidencve.

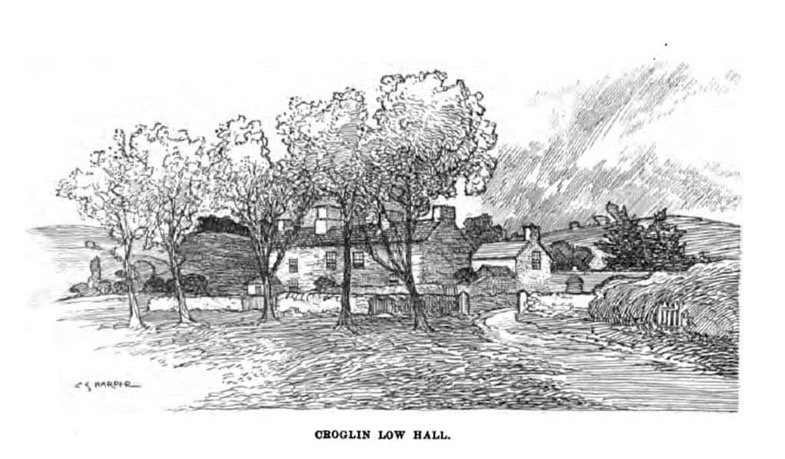

Croglin High Hall or Croglin Low Hall?

One of the trickiest things about this story is that there is officially no such place as Croglin Grange. The picture above is a sketch of a farmhouse in the Eden Valley in Cumbria called Croglin Low Hall, which is the nearest the hauntologists (yes, actually a job) have come to discovering the location for this vampire story.

In the story, Hare, or Captain Fisher as the narrator, specifies a couple of things about Croglin Grange. Firstly, it has a chapel in the grounds, or at least within sight of the windows of the house. Secondly, it is only one story high. This is very important for the action of the story because I would be vampire appears to have no supernatural powers- unless you count rising from the grave and the ability to pick the lead out of window panes. So for him to access the bedroom of the poor woman he attacks, it is going to have to be on the ground floor. The story labours this point quite a lot a the beginning.

But here’s the thing. There aren’t any one story farm houses in this area of the Eden valley with attached chapels. Charles G. Harper, the expert in haunted houses, did go to the Eden Valley to see if he could find Croglin Grange. But all he found was Croglin High Hall and Croglin Low Hall, neither of which had a chapel and both of which had a second floor.

It wouldn’t be until much later that Croglin High Hall was identified as the probably location for the story. Further research in the 60’s by Francis Clive-Ross (read an account by his friend Richard Whittington-Egan here) discovered that Croglin Low Hall had been called Croglin Grange until the late 18th century

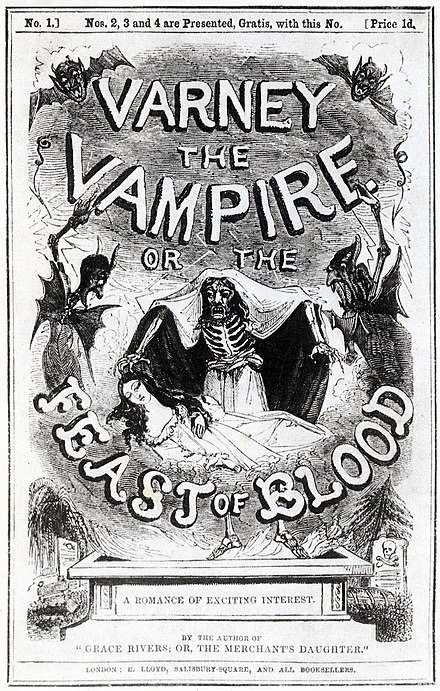

A variation on Varney

Anyone reading The Vampire of Croglin Grange for the first time might experience a certain sense of familiarity: the frightened young maiden woken from her sleep, the fiend that crawls in through the window in search of blood and ravishes of said maiden in her bed. It is a trope now so familiar to us that almost anyone would leap up and cry ‘Dracula’ just from those tiny hints.

While what I’ve just described could indeed be a description of Dracula, it could equally describe the story of The Vampire of Croglin Grange and Varney the Vampire; or The Feast of Blood. And what’s more, Varney pre-dates either Croglin or Dracula.

Originally published in 1845 as a cheap ‘penny dreadful’. The story is set in both England and Italy and tells the tale of the vampire Sir Francis Varney. Across the course of 232 chapters (and you though Augusts Hare was long winded) Varney torments maidens, drinks blood, schemes for monetary gain and eventually commits suicide by throwing himself into Mt. Vesuvius.

Like all penny dreadfuls, the story is wildly inconsistent and sensational. But it does give us our first glimpses of a Dracula like character. Varney isn’t the first vampire in English literature (that position belongs to John Polidori’s The Vampyre) but it is the first to show some of the tropes that will later become popular in vampire fiction: helpless maidens ravished, ennui with eternal life and those pointy fangs for sucking blood.

If you want to have a go at reading Varney, Project Gutenberg has all 232 chapters for you to enjoy.

A touch of Dracula

The big question remains, does Croglin owe anything to Dracula? Well, it is difficult to read Hare’s story without having flashbacks to Stoker’s masterpiece.

Published in 1897, Dracula was an instant hit but sadly made very little money for the writer because of contract issues and copyright problems. It has never been out of print since the first edition, and the characters now inhabit the public consciousness with a power that is almost supernatural.

Would Hare have been aware of Dracula? Undoubtedly. By the time Hare is revising the second volume of Story of My Life for publication in 1900, Dracula was everywhere- thousands of copies had been sold, it had been serialised in magazines and Stoker was widely talked about in literary circles.

Dracula wasn’t the first vampire tale but it is the most enduring. It entered the Western psyche, in a way few stories ever do, with a heady mix of gothic dread, modern angst and sex. If you were August Hare wouldn’t you want to borrow some of that for yourself?

If you haven’t read Dracula then there is a great hardback edition by Puffin books available here.

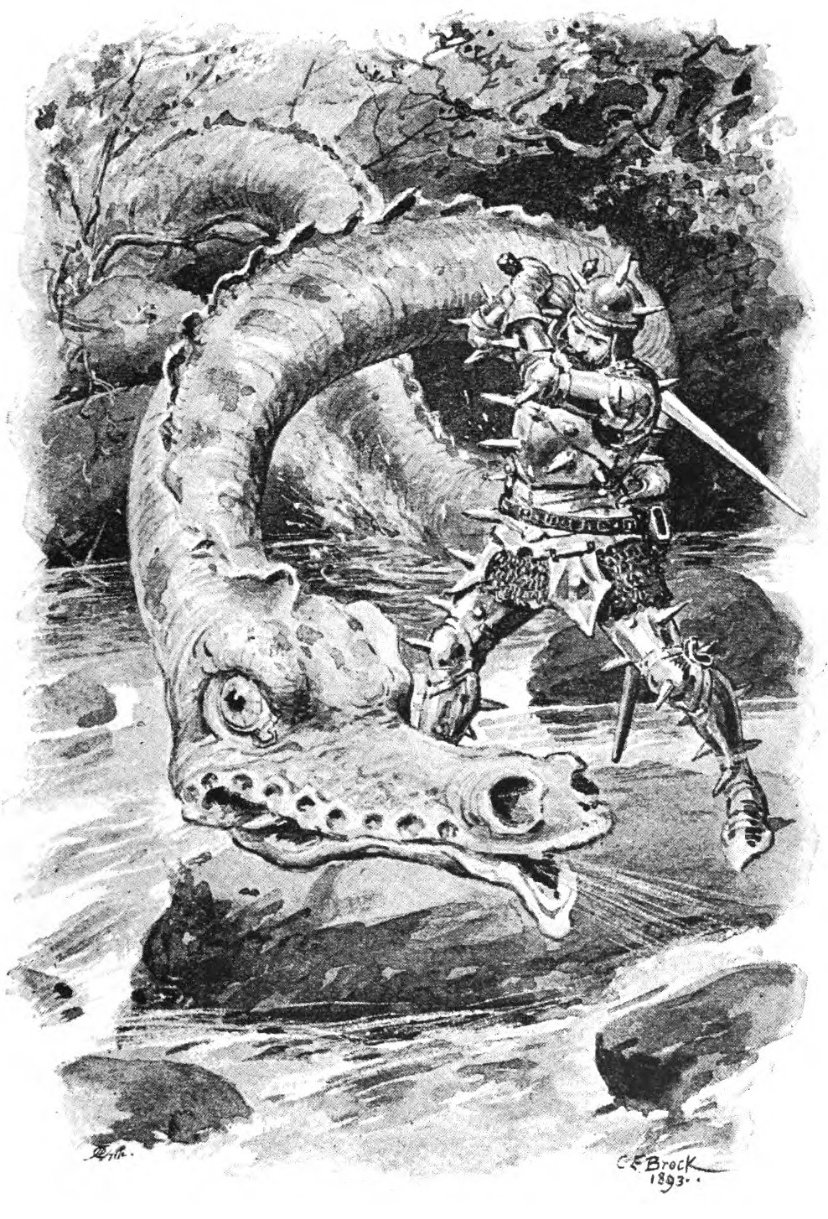

1.4- The Lambton Worm

Wyvern, worm or dragon? The moral of Durham’s most famous folktale explores faith, family and acts of repentance.

Worms, wyverns and dragons! In Episode 4 we’re exploring one of the most infamous tales from the North of England; the Lambton Worm. Is it a story of folly, a warning against unchristian behaviour, or simply a popular legend reworked for a new audience?

A Worm Not a Dragon?

Worms (sometimes Wyrms), distinct from the classic dragons because they were often depicted as having no wings or no legs (sometimes neither), are a staple of Northern English folk stories but the Lambton Worm is undoubtedly the most famous. In fact the descriptions of Worms appear closely linked to rivers and you might note the descriptions - long sinuous bodies, horse-like heads and multiple nostrils or whiskers - are startling similar to the water dragons of Asia.

Why Lambton?

Lambton is intrinsically linked to worm legends. In Chester-le-Street you can visit pubs and shops named for the story or take a stroll up Worm Hill, which the creature was said to have encircled with its massive body. There’s even a song and more than one poem. That wasn’t always the case though, in our research this week we came across the likely original tale from the 16th Century called the Sockburn Worm. Both originate in Durham, but have very different heroes with the Sockburn Worm including an Ethiopian army while the Lambton Worm becomes the nemesis of John Lambton.

While the Sockburn Worm story has plenty to recommend it (you can check it out here) it’s the unusual and yet familiar structure of the Lambton story that is so fascinating. Rather than a tale of simple heroics and reward, the Lambton Worm is closer to a tragedy. It sends a strong message that if you do wrong, it is your responsibility to right it and you may not get the happy ending you desire. It’s filled with wonderful warnings about the folly of overconfidence and immorality.

Chivalry & Folk Legends

A key influence on the change in tale and its reworking for a new and simple hero is probably the interest in the idea of a golden age of chivalry, where knights and lords were protectors of their people. We see that strongly in the Lambton story. John is a returned crusader and his father, to defend the local villages, has beggared his estate to feed the worm. It is also John and his father that become solely responsible for defeating the monster and the Lambton line that bears the curse to never die in bed at peace when John refuses to become a kinslayer. This aligns much more closely with the wonderful tales of knights and Arthurian legend being produced during the 19th Century when the story became popularised than earlier recounting. It also makes it fairly obvious that more than a bit of the reworking was probably because of the real John Lambton, a revolutionary man who supported better working conditions, universal suffrage and education. Why wouldn’t a real lord who campaigned tirelessly for the rights of the common people have an ancestor so thoroughly self-sacrificing?

With so much context, it was a challenge to pick the best possible angle to write from this week. So check out the episode and let us know if you think we’ve captured the essence of the Lambton Worm.

1.3- Cormoran the Giant

Giants, Trojans and Jack the Giant Slayer. This episode takes a look at how the theme of conflict links many stories surrounding St. Michael’s Mount.

Epsiode 3 sees us take a dive into the lives of the last of the giants and the making of St. Michael’s Mount. And we ask price a home in the restless bay?

For this week’s blog post we’re going to share with you some links to the fascinating sources we used as part of the research for our stories. Prepare yourselves for a deep dive into 18th century chapbooks, stone hearts and wandering classical warriors.

To Jack or not to Jack?

One of our biggest dilemmas this week was whether or not to focus on the Jack the Giant Slayer aspect of Cormoran’s story. While this is probably the more famous part of the tales surrounding St. Michael’s Mount, it is also part of a longer tale created for readers of late 18th and early 19th century chapbooks. Jack’s exploits take him through a series of encounters with different giants across England and Wales, using his cunning to destroy them and save helpless maidens. It is classic fairytale.

If you want to look at an original chapbook from Scotland, you can follow this link to the National Library of Scotland, where you can look through a digitised copy of the Jack the Giant Killer story.

But this isn’t Jack’s tale. We wanted this episode to be focused on Cormoran and Cormelian and the mount.

A view of Chapel Rock looking out towards the mount.

The Green Rock of the Bay

The thing which fascinated us both about the mount was the old folk legend that it came from inland Cornwall, with the Cornish name for the mount being Carrick Los yn Cos- The Grey Rock in the Wood. Just this image was enough to spark off our imaginations. Especially when we discovered that the legend is that Cormoran and his wife Cormelian were said to have transported the rocks from a wood somewhere inland to the bay. This got us thinking about the motivation for the giants to undertake such a mammoth task. Why build a home for themselves so far from the shore?

One of my favourite parts of this story is the creation of what is now known as Chapel Rock. In the original legend of the creation of the mount, Cormelian- who is doing almost all of the heavy lifting in her giant apron made of a dozen bull hides- grows tired of trudging back and forth to the wood for the good grey granite. When her husband is sleeping off his lunch, she decides to forgo the long walk back to the woodland and instead picks up a large green stone from the shore near the mount. Sadly, Cormoran wakes before she has taken more than a few steps from the shore. Furious at her laziness, he either throws his hammer to make her drop the rock or kicks her in the back. Either way, Cormelian drops the green rock half way between the shore and the mount.

In later years the monks who came the the mount after the Norman conquest would build a small chapel on that green rock, thus making it Chapel rock.

Brutus and New Troy

One of the main inspirations for both stories was Amy Jeff’s Storyland. This beautifully illustrated book tells the legends of Britain as passed down through writers like Geoffrey of Monmouth and Gerald of Wales. We love the mix of illustration, exploration of primary source material and Amy’s writing. Order Storyland at Sherlock and Pages via this link.

One of the stories retold in the book is that of the arrival of Brutus and his band of Trojans in Britain and the founding of New Troy. When the Trojans arrive, they find the land inhabited by hot-blooded giants. the conflict is instant and a war begins. Brutus and his friend Cornieus fight the giant Gogmagog for control of the isle. in the end Cornieus challenges Gogmagog to a wrestling match and throws him over the cliffs- to his death or not it is not clear. The result of this victory is the renaming of that land after the victor- Cornwall.

Some sources make a parallel between Cormoran and Gogmagog. And this got us thinking about conflicts, leading to two stories themed around the mount as a refuge.

1.2 The Leap Castle Elemental

So many spirits and so little time. Do you dare enter the most haunted castle in Ireland?

Many spirits wander Leap Castle, but none so terrifying as the spectre known only as The Elemental.

When we were planning this episode we came across dozens of tantalising stories about Leap Castle and the spirits who roam its halls. In fact, there were so many that it was quite difficult to pin down the episode to just one story. In the end, Mildred Darby’s tales of her encounters with the Elemental (listen to the episode for more details) won us over with its gothic mix of Victorian spiritualism and domestic drama. But this meant that we didn’t quite have time to talk about all the druidic curses and fratricide that make Leap Castle the ideal setting for a horror story or two. Here are the bits we didn’t completely cover in the episode.

Leap Castle as a druidic site.

Legend has it that Leap was once the site of druidic ritual. Some suppose that this could have been the origin of the Elemental. The thinking goes that the Elemental is a nature spirit used by the druids in their spells or set there to protect the site. Those who map out magical energy have said that the castle sits on the crossing of two ley lines, which would have made it a natural location for druids to pick for rituals.

2. The Brothers in the Bloody Chapel

Give the age of the castle, it is not surprising that there are many stories of skullduggery and murder associated with various rooms. The most famous of these was one of our top contenders for a re-telling: the tale of the two O’Carroll brothers whose struggle for control of their clan after their father’s death led to a violent and deadly confrontation in the castle’s chapel. One brother, a priest, was giving mass, when another brother stormed in and mortally wounded him. This room in the castle is associated with smells of rubber and blinding lights pouring from the windows, even in the days when it was an uninhabited, burned-out shell.

3. The Red Lady

One of the more tragic stories connected with Leap Castle is that belonging to the so-called Red Lady. This spirit makes a brief apprence in The Unwilling Guest- the tale in which sceptical Mr. Irving comes face to face with the Elemental. The legend goes that this Red Lady was a captive or relative of the O’Carrolls who become pregnant. When the child was born it was decided that there were already too many mouths to feed and the baby was murdered by the family. In the original tale the woman kills herself with the dagger that she carries as a spirit. She is said to haunt the rooms that were used a the nursery. There’s a first hand account from one of Mildred’s guests at Leap on the Leap Castle website.

A photograph of Mildred Darby on her wedding day (taken from the Offaly History blog)

4. The Writings of Mildred Darby

Writing under the pseudonym of Andrew Merry, Mildred wrote many novels and short stories, mostly focused on her home in Ireland and the people around her, including the lives of her tenants and the poor in Ireland. Her works include ‘Kilman Castle: A House of Horrors’ in which she told a fictionalised account of an encounter with an elemental spirit. Jonathan Darby disapproved of his wife’s writing but it wasn’t until she wrote The Hunger ( a novel about the lives of the poor during the Irish famine) that he forbade her to continue publishing her work. There is a much more detailed account of this on the Offaly history site.

5. The Oubliette

Popularised in the bloodthirsty wars of the medieval period, these ‘forgotten rooms’ were used as the ultimate form of torture and execution for troublesome enemies. Essentially, they were deep, narrow pits, often not wide enough to crouch down. Prisoners were lowered (or pushed) through a trap door and left there until the lord of the castle decided to release them. Many were left to rot in there, dying of either hunger or starvation. The oubliette at Leap Castle seems to have been a particularly gruesome example, with the floor covered in sharp spikes (perhaps to hurry along those prisoner to their graves). The story goes that when the oubliette at Leap was excavated during some improvement works to the castle the workers found the bones of nearly 150 individuals, including one carrying a pocket watch from the early 19th Century. No wonder then that the castle is one of the most haunted places in Ireland.

1.1 The Rollright Stones

Magic, ambition and a terrible curse. This strange folk tale has it all.

On a long stretch of A road just outside Chipping Norton there stands a collection of neolithic monuments with a fascinating history.

Listen now to episode one of Wyrd Folk to find out how a meeting between an enchantress and a would-be king ends with a terrible curse.

We chose the legend of how the Rollright Stones were formed as our first episode because it has such a fascinating history. But we didn’t quite have time in either of our stories to include everything. So here is the rundown of our favourite folklore beliefs about the Kingsmen, the King’s stone and the Whispering Knights.

1. The Stones are uncountable

This part of the legend is the one that makes the most logical sense. Anyone who has ever visited the Rollright Stones can tell you that the stones are so weathered and tumbled down that the original upright dolmen have crumbled into pieces over time. Anyone attempting to count the stones finds themselves confronted with many jagged pieces of rock that lay so tumbled together that only the particularly observant can recall which stones they have already counted and which they have not.

2. Removing the Stones is dangerous.

In the episode, we briefly talked about the local story of a farmer who removed one of the stones to make a bridge for the stream at the bottom of the hill. Local folklore tells that it took 24 men to drag the stone out of place and to the stream, killing one of them in the process. But by the next morning, the stone had tipped itself out of position and onto one side of the bank. This continued over and over again until the farmer’s crop also failed and he decided it would be wise to replace the stone, which then slipped easily up the hill and back into its previous spot. We can easily believe that removing a stone from a sacred site would bring down this kind of curse.

3. A Site of Pagan Worship

The Rollrights have such a powerful connection with witchcraft that it is still used by local covens as a gathering place for special events. This area of North Oxfordshire has a strong association with witchcraft and it is quite common to see an offering (like the one pictured above) in the centre of the circle or placed on to the stones of the Whispering Knights.

4. Drinking Stones

Local legend has it that the King’s Stone (pictured above) and his knights in the stone circle get up at midnight and make their way down to Little Rollright Spinney to drink from the water of the stream. We can certainly see why they might be thirsty after a few thousand years as a hoar stone! This kind of legend is quite common with standing stones, with very similar legends being shared about standing stones in Worcestershire and Herefordshire.

5. The Wood of the Whispering Knights

This fact is not a legend but comes from the archaeological evidence excavated from around the Whispering Knights. Soil analysis suggests that the knights, which are thought to be the collapsed portal dolmen for a burial barrow from around 3,500BC, might have been erected in a woodland glade. The Whispering Knights are the oldest of The Rollright Stones and were erected before the clearing of large swathes of forest for agriculture. We love the idea that these stones were once the portal to a tomb which sat in a woodland glade on the hill.